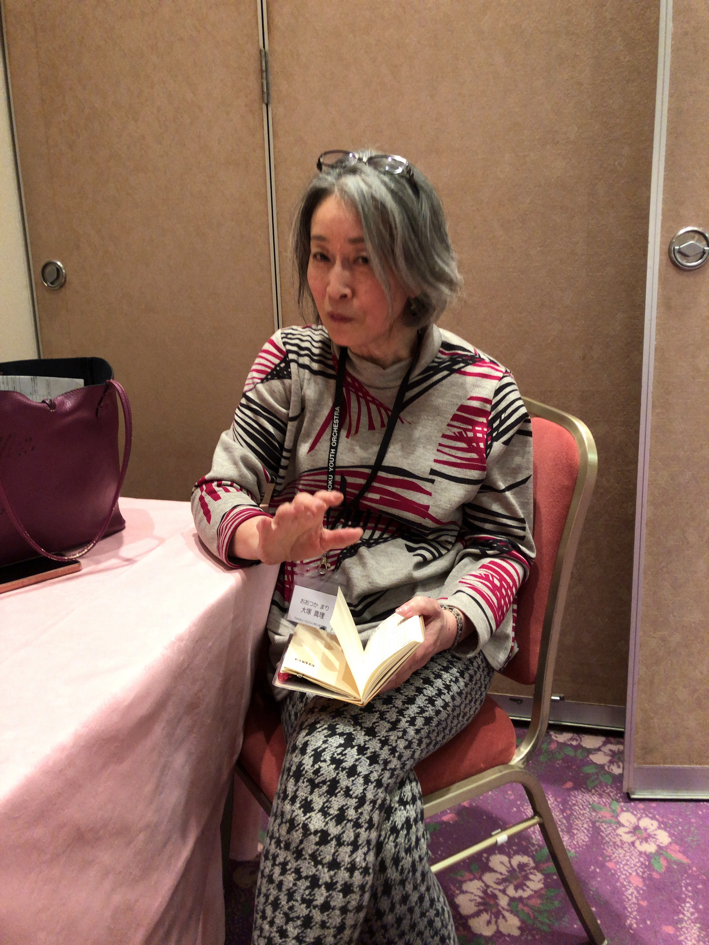

Mari Otsuka from the Fukushima Secretariat spoke at length.

Mari Otsuka from the Fukushima Secretariat spoke at length.

The Tohoku Youth Orchestra was formed when the Lucerne Festival, a world-renowned music festival in Switzerland, approached us about holding a recovery event for the Great East Japan Earthquake.

The Children's Music Revitalization Fund has been inspecting and repairing musical instruments in schools in the three affected prefectures and supporting musical activities since immediately after the earthquake. Ryuichi Sakamoto, the fund's founder, came up with the idea of forming an orchestra made up of children.

If there is an opportunity to form a mixed orchestra called the Tohoku Youth Orchestra and perform with conductors Gustavo Dudamel and Ryuichi Sakamoto at a music event in Matsushima, Miyagi Prefecture, sponsored by Lucerne in 2013, the images of local children who are in the process of reconstruction could be conveyed not only to Japan but to the world.

The person who accepted this big idea was Mari Otsuka, who was in charge of the secretariat of the FTV Junior Orchestra, which was run by Fukushima Television, a television station in Fukushima City at the time. Without her, the Tohoku Youth Orchestra would not have been born at the Lucerne Festival Ark Nova Matsushima 2013. In that sense, Mari Otsuka is the mother of TYO.

Since then, from running around the local area with flyers in hand to recruit members in 2015, to dealing with sudden illnesses at training camps, to cleaning up the trash generated by members at monthly joint training sessions in Fukushima City, we have received thoughtful support in every aspect. Whenever the topic of the nuclear accident came up, they would speak in a loud voice about the response of the government and TEPCO and the serious impact, and we would talk to them from time to time. However, we realized that we had never had a so-called "interview" with them. So, this year, as 3/11 approached, we spoke to them over two days at a two-day joint training session in February.

- Today I would like to talk to you again. First, can we start with the story of when you joined Fukushima Television (FTV)?

I joined FTV in 1977, the 52nd year of the Showa era. I started out in the Sales Management Department, where I was assigned to the Spot Desk.

(Note: The "Spot Desk" is the section that manages the spot commercials that appear between programs.)

After that, I became a sub-director in the production department. I was in charge of the prefectural office and produced "City News" and "Small World," an early childhood education program for mothers. I called myself the "bento director" because I was always arranging bento and flowers.

At that time, there were programs for the Junior Orchestra, such as the drum and fife corps parade. It was a 1.5 hour program every Saturday afternoon, and it had sponsors. In the past, there were quite a few programs produced in-house.

- Nowadays, local stations only broadcast the programs of major Tokyo stations. Was Fukushima TV a Fuji TV network station even back then?

At that time, Fuji TV and TBS were the two networks. It was the best. The Drifters' "It's 8 o'clock, All Together," "Kao Meijin Gekijo," "The Best Ten," "Yoru no Hit Studio," the Kinpachi Sensei drama, and "Naruhodo! The World" were all broadcast on the same network.

- That's amazing! Those are all shows I watched when I was a kid. I'm sure your work was really interesting too.

Yes, it was fun, so I ended up working there for 10 years before getting married. At the time in Fukushima, people over 30 were considered to be late in getting married, so people around me were worried about me (laughs).

- So, quitting your job to get married is quite rare these days. You quit your job and then returned to work.

When my husband passed away, they asked me to come back. About 15 years ago, they asked me to help them with the paperwork because they were in a difficult situation.

- When I'm in trouble, I turn to Mr. Otsuka (laughs).

In 2003, I worked as a contract employee in the business department of Fukushima Television for a year. Then, the following year, in 2004, I was asked to run the FTV Junior Orchestra secretariat. By that time, there were almost no female employees at Fukushima Television.

-Have you had a connection with the orchestra for a long time?

When I was in the production department, I had helped out a few times as a timekeeper during the recording of a junior orchestra program. So when I was asked, I said, "Oh, an orchestra? I don't know anything about music, but I can do clerical work and budget management."

I know the people in the company well and can negotiate within the company. Also, I was trained in sales and production, so I know the process well. I really think that nothing in life is a waste of experience. My experience when I was young was useful.

- That's a great fit for you, Mr. Otsuka. But running an orchestra also requires specialized knowledge, right? What did you do?

To begin with, I didn't even know the difference between a trumpet and a trombone. So I read books desperately. I read music magazines like "Ongaku no Tomo" every month, and read books about Furtwängler, Karajan, the Vienna Philharmonic, and others whenever I felt like it. I think the books by Daisuke Mogi, an oboist at the NHK Symphony Orchestra, were particularly helpful.

I couldn't understand what the teachers who taught me were saying, so I made a German-Italian comparison chart so that I could read music. I also listened to all the introductory CDs, such as "Easy Classical Music."

— Running an orchestra involves some tasks that are unique to this world.

First of all, I worked hard to organize the scores. They were all in disarray. I was taught by my percussion teacher, Keiko Otsuka, who came from Tokyo to teach me how to arrange the parts and how to number them, which was very helpful.

I think I'm finally getting used to it after three years. I've started to understand things like budgets, instruments, and technical terms. Gradually, I've started to enjoy the work, and I've become able to come up with ideas on my own.

— Was there a turning point for you in the junior orchestra?

I think it was the 6th or 7th year. We did a full-length Tchaikovsky's "Nutcracker" with the Hitomi Takeuchi Ballet Company as a Christmas concert at the Fukushima Prefectural Cultural Center. When we proposed this project, the teachers were against it because the children would be playing in the orchestra pit and would be playing supporting roles. But the children said they wanted to do it. So we pushed through (laughs). We divided it into two parts to reduce the burden on them.

--What is your most memorable concert?

Beethoven's Symphony No. 9. It was December 30, 2013, the year I left the FTV Junior Orchestra secretariat. The venue is a prefectural public facility called the Fukushima Prefectural Cultural Center, so the last day of work at the end of the year is usually the 28th. I asked them to open it, which was the first time in the hall's history.

This time too, adults were against it. They kept saying, "We're busy, it's impossible." But when we asked the children, they said, "I want to try." They can actually do it. When children say, "I'll do it," they do it. Adults shouldn't decide.This is what the children taught me. Children are amazing. I have been living my life with the power and help of young people. Two years have passed since the Great Earthquake, and I also have feelings for the reconstruction of Fukushima.

I said that I would quit my job in the junior orchestra in 10 years. My children were graduating from university, and I had decided that I would live freely from the age of 60 onwards. That's why I wanted to end my career by performing the Ninth Symphony, which is the "Ode to Joy". I was told that the Ninth Symphony chorus would be difficult because it was an open recruitment, but I could do my best because it was something I loved. And I was blessed with teachers and people around me who supported me.

Thanks to you, the concert was a great success.

— This is a question I always ask in interviews with members. Where were you and what were you doing on 3/11?

I was alone in the office on the fifth floor of the old Fukushima TV building. 2:40 was always the time when I finished work. So that day, I got up to make some coffee, and my cell phone rang with an earthquake alarm. I was shocked by the violent shaking. I ran down the hallway to escape, but I couldn't move forward as I wanted. Then the wall started to collapse in parts. The music stands all fell down with a bang, and I couldn't go down the stairs, so I held on to the pillar in the corner of the elevator. Then, behind me, the copy machine ran left and right. I was so shocked that I thought I was going to die alone.

The second shaking was stronger and felt longer. Meanwhile, the head of the secretarial office on the fourth floor came up to stop the fire doors that were slamming loudly.

When the shaking subsided and I returned to the business department on the third floor, I was told to go outside because it was dangerous. When I went outside, thunder and snow started.

The new building, where the news and production were located, didn't sustain much damage, but the old building was a disaster. Almost all the glass and windows were broken, so the building was covered with plywood for a long time after that. People said it was a miracle that no one was injured. The walls were cracked, and all we could do was laugh and say, "It looks like a melon house."

— Have you been outside for a while?

I was told to go home for a while. I contacted my family to check if they were safe. Then, I returned to the office on the fifth floor, but the TV and fax machine had been blown away. Finally, I found my bag and shoes, grabbed my coat, and got into my car. I heard on the radio in the car that a tsunami had occurred. They said there was damage, but I didn't really understand. Even though I was driving, the traffic lights were out, so there wasn't any traffic jams, but I couldn't even cross the road as I wanted, so I had to ask other cars to let me pass, saying "excuse me," and I chose a road without a railroad crossing to drive on.

When the water pipe burst, I couldn't see the roads anymore, and my legs were shaking while I was driving. I was so scared that my house was gone. I was so scared when I had to pass by the side of the road that had collapsed and my minicar had fallen. I'm still scared when I think about that time.

Thankfully, our house still stood and the roof was not damaged, but our electricity, gas and water were cut off.

- Was everyone in your family safe?

At the time, my eldest daughter, who was 23 years old, happened to be off work at the bank where she worked, so my usually absent-minded daughter ran out to 7-Eleven to buy some groceries, but reported to me that there was almost nothing left.

My 78-year-old father apparently left the house holding the dog to stop it from jumping out.

My 80-year-old mother was unable to move at the entrance. She said she was so shocked that she has no memory of it. She said she just sat there in a daze.

I was able to confirm that my family and home were safe, and when I reported to my company, I was told that I didn't need to come to work for a while. It was a Friday, so I stayed home for a while after that.

— Did you find out about the tsunami later?

The only information we had was on the radio. So even when we heard about the tragic situation of the tsunami, we couldn't imagine it. After the electricity came back on, we were shocked to see the tsunami on TV. It was like a scene from a movie. We thought, "This kind of thing really happens." We were thankful that everyone in our family was alive.

Did you go to an evacuation centre?

In the end, I never went to an evacuation shelter. We were told that the electricity would be cut off in the event of the Y2K problem, so we had a stove and kerosene, which helped us to avoid the cold. We also got water from a nearby well that was not drinkable, boiled it on the stove, and made hot water bottles, which we then used to use the toilet.

We had heard that there was drinkable water from a well in the neighborhood, so we kept our car running as long as we had gas.

As expected, water and electricity were a problem. At night, we had to bring solar-powered lights from the garden into the house or rely on candles. We couldn't watch TV.

Gas was the first to come back on, and it took less than a week. Water took a week. And electricity was the last to come back on at our house. There was electricity on the other side of the road, so it was heartbreaking to think we were so close to getting it back on. Electricity, gas, and water were all fine in the town, though.

— When did you find out about the nuclear accident?

I went to work on Tuesday, the first day of the week after the earthquake, and for the first time I learned that the nuclear power plant was in a terrible state. Until then, I hadn't thought of it as such a serious matter. When I got home, I wondered, "Where should I evacuate? Which direction? I should take my valuables with me, and be prepared to evacuate at any time."

People would line up outside for two hours just to get water. I didn't think nuclear power was serious. Children were out of school, so they were lining up outside. Looking back, I wish they had told us a bit more. I wonder if there were better ways to publicize it. I'm sure we probably didn't have time for that. It was something that no one had ever experienced before. There had been no disasters in Fukushima, so we assumed it was a disaster-free prefecture. We also assumed that "nuclear power plants are safe." The earthquake aside, the horror of the tsunami. I wish that tsunami hadn't happened.

— Did you ever try to flee Fukushima City?

Even if we escaped, we would have no place to live. We tried not to go outside as much as possible, with the windows closed. We drove while we still had gas. We decided not to go outside unless it was absolutely necessary.

Even so, the aftershocks continued for a while. We continued to live in fear of earthquake warnings. We wore tracksuits both at home and when we slept, and lived in a Japanese-style room on the first floor so that we could go outside at any time.

I wonder when life returned to normal. Memories tend to become vague.

— This is also a question I always ask in interviews with members: what has changed since 3/11?

I've come to feel grateful for the things that allow me to spend my days without incident. I'm grateful for electricity, gas, and water. And I'm grateful for everything.

Ordinary is best, normal is best.

I think I have become more calm now, as I have learned to say "thank you" to everything and feel grateful.

Since then, I've started to prepare for disasters on a regular basis. Even so, I think I'd panic if it happened again.

— Have you noticed any changes in the children who are members of the FTV Junior Orchestra?

Among the junior children, three left the group due to self-evacuation. Conversely, one child who evacuated from Namie Town joined the group. Three Fukushima TV employees with small children also left the group.

Even in Fukushima Prefecture, radiation levels are high in unexpected places like Iitate Village and Date City. The young people who left probably won't come back. There are only old people now. People can't live in the evacuated areas. There are no shops or hospitals.

— What do you think about Fukushima right now?

They say they will build a new junior and senior high school in Fukushima Prefecture, but I think it's just to deceive the public. I also have a lack of trust in the government. No matter how much Prime Minister Abe presents that "the nuclear accident is under control" in order to attract the Olympics to Tokyo, I think, "He's lying!"

Even if they say they have decontaminated, I think there is a limit to how much they can do, because wild boars, pigs, and other animals roam the mountains and eat contaminated food.

— You said that decontamination work had just arrived recently.

Finally, at the end of last year, they came to decontaminate the drains in my neighborhood. There is still decontaminated soil in my yard. It's a big bag, so it's depressing to see it. They don't take it away.

(This is a photo of the decontaminated soil left in the garden of Mr. Otsuka's home.)

They started in areas with high radiation levels, and then came to my house about a year later and said, "It's probably pointless to do it now." It feels like a consolation.

— I wonder what the reality is.

I've heard rumors that the number of cancer patients is increasing, but it's not really coming out in public. Looking at the recent "fraudulent statistics" issue in the country, I think people's trust in information is declining. I think they're only announcing what's convenient for them and are controlling the information.

Someone from Okinawa told me, "The people of Fukushima are so quiet." In Okinawa, there are demonstrations every day (laughs).

— Is there anything you would like to ask the government or national authorities to do?

I want the truth to be announced. I want to know what is happening now. No matter how many dosimeters there are in the city of Fukushima, I think it's just a placebo effect.

Moreover, after causing such a terrible accident, they tried to sell the nuclear power plant to an overseas country. What on earth do they think about Fukushima?

It makes me sad to wonder what the country is thinking.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki are the only countries to have suffered atomic bombings.

Japan today is sad.

— Despite this, the Tohoku Youth Orchestra is still active. What do you think about this?

Since the main focus is on children, I don't think adults should impose political opinions on them.

But Ryuichi Sakamoto, the team's director and president, speaks his mind. I think he's great and courageous. It's important for influential people to make statements.

Mr. Sakamoto, I think you're amazing and I always respect you.

— The Tohoku Youth Orchestra was born because the FTV Junior Orchestra's activities continued even after the earthquake.

After the disaster, there was talk of stopping the Junior Orchestra's activities. But the kids wanted to continue. However, the old Fukushima TV building, which they used for practice every week, couldn't be used. Practices resumed a while after the May holidays in 2011. We moved around a lot, carrying our instruments every week and continuing to practice. Sometimes we practiced in a conference room at an affiliated company. Then, in July, we were able to hold a regular concert. It was a good job. The kids said they definitely wanted to do it. We also had the support of the parents. Thanks to them, we were able to hold a concert right after the Fukushima City Music Hall reopened.

— The Tohoku Youth Orchestra started as a part of the Lucerne Festival's revival event in 2013. You were the driving force behind that.

I was completely absorbed in the 2013 Lucerne event. I think I did a good job. I had the energy to do it now for my children. It was a time when it was easier for me to do something. It's no good if you stop.

If I had the chance, I wanted to take my children somewhere outside of Fukushima. And to open their eyes to the world. To get to know all kinds of people. I thought the Lucerne reconstruction event would be the perfect opportunity to do just that.

However, the teachers at FTV Junior were also against it. They said it would be a burden on the children. Adults always choose the safe route. There is no other opportunity like this to connect with the world. We asked not only FTV Junior but also the brass band club of a nearby high school to send as many children as possible.

I think I was able to have a great experience working with world-famous people like Dudamel and Ryuichi Sakamoto in the special place of Matsushima.

It was great to see the children smiling with joy after getting Mr. Sakamoto's autograph.

—Due to the positive reception at the Lucerne Festival, the Tohoku Youth Orchestra has become a general incorporated association.

It's good for an organization to be strong. I'm grateful that it has continued, and more than anything, it has earned the trust of parents and society.

When we first started recruiting people from scratch, I was worried about whether we would be able to get enough people. To be honest, I was surprised at the number of applications, which was over 140.

— It's been five years since the Tohoku Youth Orchestra was established. It's quite moving.

After all, the first summer camp was in Miyakojima, Okinawa Prefecture. You have amazing drive. I admire your ability to make all your dreams come true one by one. At first, the management was a bit shaky, and I wondered what would happen. But you were so enthusiastic about creating an environment where the children could concentrate only on playing. It's fine now (laughs).

— Finally, this is a question I always ask in interviews with members. What kind of activities do you want to do with the Tohoku Youth Orchestra in the future?

Children who have graduated from the group come to practice sessions and concerts, don't they? I think it's wonderful that there is such a place. So I want it to continue for a long time.

I would like to see them perform overseas. It would be great if the Tohoku Youth Orchestra, which started as a toddler, could make a triumphant return to the Lucerne Festival. Wouldn't it be great if the orchestra from the Lucerne event in Matsushima in 2013 had grown to be this impressive?

It would be nice if we could also perform in Taiwan, which was one of the first places to provide generous support and has a large number of pro-Japan people.

Are you doing anything at the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics?

This interview took place at a two-day, one-night joint practice session last month. After finishing practice on Saturday, Otsuka and Takeda Manabu, who also works in the Fukushima office and provides performance guidance to the band members, were seeing them off as the bus headed off to the accommodation for the overnight group, arranged by JA Kyosai.

Listening to Mari Otsuka's story, I was reminded of her strong sense of mission and her unconditional love for children. Her underlying attitude is that "adults don't understand children, or their potential," and so there is not even a trace of condescending condescension in her gaze towards children. It's very casual. That's why I think the children are able to sense Otsuka's stance in an animal-like way and naturally come to her.

"Don't think about children for the sake of adults" is a phrase we should keep in mind. At the same time, it's childish to want to say, "Children should think about adult circumstances, too." I'll reflect on this.

Some of the things we actually heard were very stimulating, and we really wanted to publish "Otsuka Speaks" uncut and unedited, but we felt that doing so would go against the dignity of the material, so we have edited it, regardless of whether we were able to take every detail into consideration.

It has been eight years since 3/11. The great earthquake continues. I want people to know that. That is one of the reasons for the existence of the Tohoku Youth Orchestra.

We ask for your continued support for the Tohoku Youth Orchestra.